PAPER – didactic supplement

ITALIAN JOURNAL WOODPIGEON RESEARCH – IJWR – 2018 IJWR @2018

Vol.1 – 2018

Publishing date march 2018

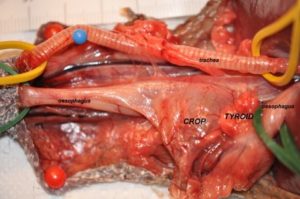

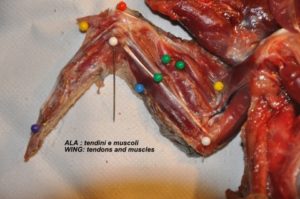

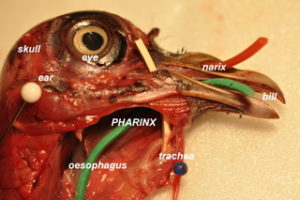

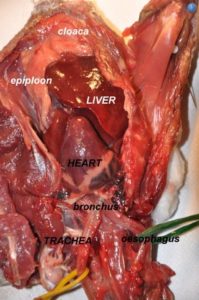

WOODPIGEON’s ANATOMY – Photographic Atlas

Cavina Enrico m.d. – surgeon – Club Italiano del Colombaccio

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/albums/5802521945641185121

Introduction

The aim of the present Atlas is only to show – quite live-real – the organs , anatomic structures ,teguments,muscles’apparatus ,anatomic details presented by a right surgical dissection . Studying the anatomy by other ancient and modern Texts and schematic designs , the reader can have here right approach by the “live” Anatomy .

Materials and method

The material is simply the body of an adult “wild” Woodpigeon and other .

The surgical dissection has been performed on a fresh body .

To explore the body’s external internal images , the reader needs to connect with didactic Links easily available on the Web by Google as listed below .

The key-words will be : birds’ anatomy , pigeon’s anatomy, wildpigeons’anatomy .

For better understanding of the images and full-anatomy we suggest to start by

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QnOiUonB1N4&sns=em

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JVekq_Ag1yA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aFdvkopOmw0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGiIlwnaNmM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWMmyVu1ueY

and attached nuomerous Youtube Links

RESULTS

Photographic atlases have the advantage….images of the actual structures themselves .

Some significative anatomic pictures by our personal surgical dissection are as following

The full ( 128 images ) approach to the Atlas of Anatomy of Woodpigeon is at :

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/albums/5802521945641185121

128 images

Special focus on PTO

All the Anatomic images by

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/albums/5802521945641185121

Particularly interesting could be the study by Comparative Anatomy as for example by ( Crow) at this Cavina/Links of the Author

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/album/6132005334176821249/6132007549265377602 (Crow )

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/album/5677109778905558449 ( Woodcock – Scolopax rusticola)

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/album/5742776865730420689 ( idem )

and by Histology ( Woodcock)

https://plus.google.com/photos/103942035281038458760/album/5633103546332622241

CONCLUSION

The message is unique as by commemorative medal of Giovanni Vitali the Italian Scientist discoverer of PTO “ NO SCIENCE WITHOUT ANATOMY “

WEB LINKS

https://sciencing.com/reproductive-system-pigeon-8564838.html

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924000932164;view=1up;seq=18

http://avianmedicine.net/content/uploads/2013/03/44.pdf

http://www.jneurosci.org/content/jneuro/22/4/RC210.full.pdf

http://pij-n-angels.forumotion.net/t571-pigeon-anatomy

https://biosphera.org/international/product/3d-bird-anatomy-software/

http://internal.champaignschools.org/staffwebsites/isabelgi/Zoology/Pigeon%20Dissection.pdf

http://www.wellcomeimageawards.org/2017/pigeon-thermoregulation

References

- Ritchison, Gary. “Ornithology (Bio 554/754):Bird Respiratory System”. Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- · Gier, H. T. (1952). “The air sacs of the loon” (PDF). Auk. American Ornithologists’ Union. 69: 40–49. doi:10.2307/4081291. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- · Smith, Nathan D. (2011). “BODY MASS AND FORAGING ECOLOGY PREDICT EVOLUTIONARY PATTERNS OF SKELETAL PNEUMATICITY IN THE DIVERSE “WATERBIRD” CLADE”. Evolution. 66: 1059–1078. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01494.x.

- · Fastovsky, David E.; Weishampel, David B. (2005). The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs (second ed.). Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81172-4. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- · Bezuidenhout, A.J.; Groenewald, H.B.; Soley, J.T. (1999). “An anatomical study of the respiratory air sacs in ostriches” (PDF). Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. The Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute. 66: 317–325. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- · Wedel, Mathew J. (2003). “Vertebral pneumaticity, air sacs, and the physiology of sauropod dinosaurs” (PDF). Paleobiology. The Paleontological Society. 29 (2): 243–255. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0243:vpasat>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- · Duezler Ayhan; Ozgel Ozcan; Dursun Nejdet (2006). “Morphometric Analysis of the Sternum in Avian Species” (PDF). Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 30: 311–314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-12.

- · Wing, Leonard W. (1956) Natural History of Birds. The Ronald Press Company.

- · Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Marugán-Lobón, Jesús; Racimo, Fernando; Bever, Gabe S.; Rowe, Timothy B.; Norell, Mark A.; Abzhanov, Arhat (2012-05-27). “Birds have paedomorphic dinosaur skulls”. Nature. 487 (7406): 223–226. doi:10.1038/nature11146. ISSN 1476-4687.

- · Louchart, Antoine; Viriot, Laurent. “From snout to beak: the loss of teeth in birds”. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 26 (12): 663–673. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.004.

- · Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Hanson, Michael; Fabbri, Matteo; Pritchard, Adam; Bever, Gabe S.; Hoffman, Eva (2016-09-01). “How to Make a Bird Skull: Major Transitions in the Evolution of the Avian Cranium, Paedomorphosis, and the Beak as a Surrogate Hand”. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (3): 389–403. doi:10.1093/icb/icw069. ISSN 1540-7063.

- · Huang, Jiandong; Wang, Xia; Hu, Yuanchao; Liu, Jia; Peteya, Jennifer A.; Clarke, Julia A. (2016-03-15). “A new ornithurine from the Early Cretaceous of China sheds light on the evolution of early ecological and cranial diversity in birds”. PeerJ. 4. doi:10.7717/peerj.1765. ISSN 2167-8359.

- · LAUDER, GEORGE V. (1982-05-01). “Patterns of Evolution in the Feeding Mechanism of Actinopterygian Fishes”. American Zoologist. 22 (2): 275–285. doi:10.1093/icb/22.2.275. ISSN 1540-7063.

- · Schaeffer, Bobb; Rosen, Donn Eric (1961). “Major Adaptive Levels in the Evolution of the Actinopterygian Feeding Mechanism”. American Zoologist. 1 (2): 187–204. doi:10.2307/3881250.

- · Simonetta, Alberto M. (1960-09-01). “On the Mechanical Implications of the Avian Skull and Their Bearing on the Evolution and Classification of Birds”. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 35 (3): 206–220. doi:10.1086/403106. ISSN 0033-5770.

- · Lingham-Soliar, Theagarten (1995-01-30). “Anatomy and functional morphology of the largest marine reptile known, Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Mosasauridae, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous, Upper Maastrichtian of The Netherlands”. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 347 (1320): 155–180. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0019. ISSN 0962-8436.

- · Holliday, Casey M.; Witmer, Lawrence M. “Cranial kinesis in dinosaurs: intracranial joints, protractor muscles, and their significance for cranial evolution and function in diapsids”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1073–1088. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1073.

- · Proctor, N. S. & Lynch, P. J. (1998) Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure & Function. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300076193

- · Lockley, M. G.; Li, R.; Harris, J. D.; Matsukawa, M.; Liu, M. (2007). “Earliest zygodactyl bird feet: Evidence from Early Cretaceous roadrunner-like tracks”. Naturwissenschaften. 94 (8): 657–665. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0239-x. PMID 17387416.

- · Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-7136-8026-1.

- · Tarboton, Warwick; Erasmus, Rudy (1998). Owls & Owling in Southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 1 86872 104 3.

- · Oberprieler, Ulrich; Cillie, Burger (2002). Raptor Identification Guide for Southern Africa. Parklands: Random House. p. 8. ISBN 0-9584195-7-4.

- · Lucas, Alfred M. (1972). Avian Anatomy – integument. East Lansing, Michigan, USA: USDA Avian Anatomy Project, Michigan State University. pp. 67, 344, 394–601.

- · Sawyer, R.H., Knapp, L.W. 2003. Avian Skin Development and the Evolutionary Origin of Feathers. J.Exp.Zool. (Mol.Dev.Evol) Vol.298B:57-72.

- · Dhouailly, D. 2009. A New Scenario for the Evolutionary Origin of Hair, Feather, and Avian Scales. J.Anat. Vol.214:587-606

- · Zheng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X. (2013). “Hind wings in basal birds and the evolution of leg feathers”. Science. 339 (6125): 1309–1312.

- · Stettenheim Peter R (2000). “The Integumentary Morphology of Modern Birds—An Overview”. American Zoologist. 40 (4): 461–477. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.461.

- · Piersma, Theunis; Renee van Aelst; Karin Kurk; Herman Berkhoudt; Leo R. M. Maas (1998). “A New Pressure Sensory Mechanism for Prey Detection in Birds: The Use of Principles of Seabed Dynamics?”. Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 265 (1404): 1377–1383. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0445.

- · Zusi, R L (1984). “A Functional and Evolutionary Analysis of Rhynchokinesis in Birds”. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 395. hdl:10088/5187.

- · Whittow, G. Causey (2000). Sturkie’s Avian Physiology. San Diego, California: Academic Press. pp. 233–241. ISBN 978-0-12-747605-6.

- · Calder, William A. (1996). Size, Function, and Life History. Mineola, New York: Courier Dove Publications. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-486-69191-6.

- · Maina, John N. (2005). The lung air sac system of birds development, structure, and function ; with 6 tables. Berlin: Springer. pp. 3.2–3.3 “Lung”, “Airway (Bronchiol) System” 66–82. ISBN 978-3-540-25595-6.

- · Krautwald-Junghanns, Maria-Elisabeth; et al. (2010). Diagnostic Imaging of Exotic Pets: Birds, Small Mammals, Reptiles. Germany: Manson Publishing. ISBN 978-3-89993-049-8.

- · Ritchson, G. “BIO 554/754 – Ornithology: Avian respiration”. Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- · Sturkie, P.D. (1976). Avian Physiology. New York: Springer Verlag. p. 201. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4862-0. ISBN 978-1-4612-9335-4.

- · Ritchison, Gary. “Ornithology (Bio 554/754):Bird Respiratory System”. Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- · Scott, Graham R. (2011). “Commentary: Elevated performance: the unique physiology of birds that fly at high altitudes”. Journal of Experimental Biology. 214: 2455–2462. doi:10.1242/jeb.052548.

- · “Bird lung”. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007.

- · Citation needed

- · June Osborne (1998). The Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. University of Texas Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-292-76047-7.

- · Zaher, Mostafa (2012). “Anatomical, histological and histochemical adaptations of the avian alimentary canal to their food habits: I-Coturnix coturnix” (PDF). Life Science Journal. 9: 253–275.

- · Stryer, Lubert (1995). In: Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 250–251. ISBN 0 7167 2009 4.

- · Moran, Edwin (2016). “Gastric digestion of protein through pancreozyme action optimizes intestinal forms for absorption, mucin formation and villus integrity”. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 221: 284–303.

- · Svihus, Birger (2014). “Function of the digestive system”. The Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 23: 306–314.

- · Storer, Tracy I.; Usinger, R. L.; Stebbins, Robert C.; Nybakken, James W. (1997). General Zoology (sixth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 750–751. ISBN 0-07-061780-5.

- · Tarboton, Warwick; Erasmus, Rudy (1998). Owls & Owling in Southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik Publishers. pp. 28–29. ISBN 1 86872 104 3.

- · Kemp, Alan; Kemp, Meg (1998). Sasol Birds of Prey of Africa and its Islands. London: New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd. p. 332. ISBN 1 85974 100 2.

- · Cade, Tom J. & Greenwald, Lewis I. (1966). “Drinking Behavior of Mousebirds in the Namib Desert, Southern Africa” (PDF). The Auk. 83 (1).

- · K. Lorenz, Verhandl. Deutsch. Zool. Ges., 41 [Zool. Anz. Suppl. 12]: 69-102, 1939

- · Cade, Tom J.; Willoughby, Ernest J. & Maclean, Gordon L. (1966). “Drinking Behavior of Sandgrouse in the Namib and Kalahari Deserts, Africa” (PDF). The Auk. 83 (1).

- · Gordon L. Maclean (1996) The Ecophysiology of Desert Birds. Springer. ISBN 3-540-59269-5

- · Elphick, Jonathan (2016). Birds: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-77085-762-9.

- · A study of the seasonal changes in avian testes Alexander Watson, J. Physiol. 1919;53;86-91, ‘greenfinch (Carduelis chloris)’, “In early summer (May and June) they are as big as a whole pea and in early winter (November) they are no bigger than a pin head”

- · Lake, PE (1981). “Male genital organs”. In King AS, McLelland J. Form and function in birds. 2. New York: Academic. pp. 1–61.

- · Kinsky, FC (1971). “The consistent presence of paired ovaries in the Kiwi(Apteryx) with some discussion of this condition in other birds”. Journal of Ornithology. 112 (3): 334–357. doi:10.1007/BF01640692.

- · Fitzpatrick, FL (1934). “Unilateral and bilateral ovaries in raptorial birds” (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 46 (1): 19–22.

- · Lynch, Wayne; Lynch, photographs by Wayne (2007). Owls of the United States and Canada : a complete guide to their biology and behavior. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8018-8687-2.

- · Birkhead, TR; A. P. Moller (1993). “Sexual selection and the temporal separation of reproductive events: sperm storage data from reptiles, birds and mammals”. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 50 (4): 295–311. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1993.tb00933.x.

- · Herrera, A. M; S. G. Shuster; C. L. Perriton; M. J. Cohn (2013). “Developmental Basis of Phallus Reduction during Bird Evolution”. Current Biology. 23 (12): 1065–1074. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.062. PMID 23746636.

- · McCracken, KG (2000). “The 20-cm Spiny Penis of the Argentine Lake Duck (Oxyura vittata)” (PDF). The Auk. 117 (3): 820–825. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2000)117[0820:TCSPOT]2.0.CO;2.

- · Arnqvist, G.; I. Danielsson (1999). “Copulatory Behavior, Genital Morphology, and Male Fertilization Success in Water Striders”. Evolution. 53: 147–156. doi:10.2307/2640927.

- · Eberhard, W (2010). “Evolution of genitalia: theories, evidence, and new directions”. Genetica. 138: 5–18. doi:10.1007/s10709-009-9358-y.

- · Hosken, D.J.; P. Stockley (2004). “Sexual selection and genital evolution”. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 19: 87–93. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2003.11.012.

- · Brennan, P. L. R.; R. O. Prum; K. G. McCracken; M. D. Sorenson; R. E. Wilson; T. R. Birkhead (2007). “Coevolution of Male and Female Genital Morphology in Waterfowl”. PLOS ONE. 2: e418. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000418. PMC 1855079 . PMID 17476339.

- · Mills, Robert (March 1994). “Applied comparative anatomy of the avian middle ear” (PDF). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 87: 155–6. PMC 1294398 . PMID 8158595. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- · R., Anderson, Ted (2006-01-01). Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow : From Genes to Populations. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780198041351. OCLC 922954367.

- · Anderson, Ted (2006). Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow: From Genes to Populations. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-19-530411-4.

- Nagy, N; Magyar, A (March 1, 2001). “Development of the follicle-associated epithelium and the secretory dendritic cell in the bursa of fabricius of the guinea fowl (Numida meleagris) studied by novel monoclonal antibodies”. The Anatomical Record. 3: 279–292. PMID11241196.

REVIEW

Consistent response of bird populations to climate change on two continents

DOI: 10.1126 / science.aac4858

Science 01 Apr 2016:

Vol. 352, Issue 6281, pp. 84-87

Philip A. Stephens1, and 32 co-Authors as by http://science.sciencemag.org/content/352/6281/84

The climate changes we are experiencing, how, how-much , where do they affect the environmental biodiversity and the life of the various species of birds? Do they bring damages or benefits?

These questions are addressed by a complex, extremely complex, all-continental research, as published recently on the prestigious magazine SCIENCE in 2016, using the integrated work of 33 researchers from Europe and North America.

The Work, as we have already said, is very complex and is articulated on complex statistical evaluations, projected also to the forecasting and use of “indices” or indicators and formulas, in fact forecasting formulas that are not easily understood by non-professionals.

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/352/6281/84

The “focus” of the Work is: <Avian Species respond differently to climate change in the two continents? >. The answer is basically “no”: in the two continents the various species of Birds respond negatively (mostly) and positively (less species of birds) in a fundamentally uniform manner in the two continents that for their spatial location (latitudes, longitudes, geomagnetism etc.) are subject to various conditions of climate change, mostly related to terrestrial overheating.

Some interesting elements emerge for the species Columba palumbus, the Colombaccio of the Western Palearctic.

Without entering into the complex aims of the Work, however, voted to identify “test-index ” linked to the biological responses of the Birds in the two Continents, we can extract and extract some data concerning the Woodpigeon .

The populations of over 150 species of birds have had various responses of decrease and increase. The Palaearctic Species Columba palumbus did not suffer from climate change but rather benefited, as seen from surveys for 13 out of 20 countries of the Western Palaearctic. In various Tables of documentation for all the Species one can read a specific “trend index” specific for the Woodpigeon , which in the 20 countries spreads from a negative minimum of “- 0.004” in Holland to a positive maximum “+ 0.121 ” in Italy . This positive status in Italy also corresponds to another datum: climate change has had negative effects for 94 avian species in Italy, and instead implies positive effects for 10 species in Italy, among which Columba palumbus.

The analysis of the “Science” article did not take into consideration many Eastern European countries that represent territories of origin for our woodpigeons , and this seems to represent a limitation of the Work, especially for Migratory Birds. However the intensity of the Woodpigeons’ Migration in Italy in the last year 2017 could also be considered as an added value to the positive “index” detected by “Science”

ITALIAN JOURNAL WOODPIGEON RESEARCH – IJWR – 2018 IJWR @2018

Vol.1 – 2018

Drafts of papers “work in progress ”

– Lavoro in ITALIANO

METEO e MIGRAZIONE degli UCCELLI : corridoi altimetrici isobarici , Colombaccio ( Columba palumbus ),eventi ed analisi interpretative .

Roberto SCHIAROLI ( * ) – CAVINA Enrico (2) ………………. ……………. …………….

(1)

(2) Club Italiano del Colombaccio

Parole chiave : Meteorologia (Meteo),Pressione Atmosferica (P.A.), isobare , corridoi altimetrici ,involi ,migrazione,organo paratimpanico (PTO)

La migrazione autunnale del Colombaccio (Columba palumbus ) in Italia ed in Europa si svolge in prevalenza in Ottobre . La fenomenologia della Migrazione è complessa ed è stata altrimenti trattata da Esperti del Club Italiano del Colombaccio ( 1997-2018) come da indicazioni in Bibliografia .

Tra i campi di Ricerca insiti nello studio delle Migrazioni è intuitivo il riferimento alle condizioni del tempo e tutti i relativi connessi fattori abiotici , tra i quali oggetto tuttora di studio è la correlazione con le funzioni supposte del c.d. “ barometro / altimetro biologico “ quale identificato nel 1911 come Organo Paratimpanico ( PTO) di Vitali , Ricercatore e Professore dell’Università di Pisa , che per questa scoperta fu selezionato candidato al Nobel negli anni ’30.

Circa la Migrazione del Colombaccio ,numerosi studi analitici – protratti per oltre 20 anni – hanno evidenziato il realizzarsi di “onde migratorie” modicamente variabili per datazione in Autunno , spesso o quasi sempre caratterizzate anche da “ PICCHI” migratori concentrati, unici od anche ripetitivi in ogni stagione in Italia ed in Europa ,fortemente condizionati dal Meteo .

L’analisi retroattiva dei “Picchi” mette in evidenza una problematica rilevante in termini di Ricerca scientifica sulle Migrazioni :

< perché –come nel caso del Colombaccio – così tanti ( migliaia ed intere popolazioni di individui ) decidono di partire tutti insieme dalle sedi di origine o di stop-over , con involi di massa quali si verificano lungo le rotte principali a varie longitudini e latitudini ? >.

Il quesito si pone prepotentemente all’interno di analisi meteorologiche contingenti.

Gli stimoli alla base di tale “ decision making “ migratorio sono vari e si esplicano in quel complesso sistema sensitivo che comprende lo status biologico dell’uccllo ( fotoperiodo sec. Latitudine-longitudine , in primis ) e tutta la c.d. “ ecologia sensitiva” . Tutti gli stimoli vanno a coordinare la migrazione autunnale – fortemente condizionata dallo status climatologico e meteorologico dell’anno – con alcuni ben definiti scopi :

- svolgere il volo migratorio in sicurezza e con quanto possibile ridotto consumo delle riserve energetiche ;

- raggiungere i predestinati luoghi di svernamento nei tempi giusti ed in condizioni corporee e “sociali” idonee allo svernamento stesso ;

- rispondere pienamente allo stimolo genetico di “salvaguardia della Specie “.

Nello specifico dei “Picchi” migratori tutti i sensi sono coinvolti ( ecologia sensitiva) per programmare e decidere il momento dell’involo , e quando tutto è pronto deve esserci un momento nel quale “ un dito virtuale preme il pulsante “ .

L’implicazione propriamente meteorologica sembra essere prepotentemente decisiva .

Alcuni studi retroattivi e ricerche anatomo-fisiologiche pertinenti indicano ormai con quasi certezza che il barometro biologico (PTO) è il pulsante sul quale agisce un fattore fisico ( il dito che preme ) identificabile in uno sbalzo della Pressione Atmosferica ( più o meno repentino o diluito 12-24-48 ore ) superiore a 10 hPa nel contesto di una situazione meteorologica che tende a stabilizzare l’atmosfera per una vasta area di Alta Pressione .

Emblematico lo sbalzo di 27 hPa nelle 12 ore precedenti l’involo e transito di mezzo milione di Colombacci , oltre a 90.000 oche e 14.000 gru , verificatosi 11 Ottobre 2013 in Svezia .

Molti altri dati similmente documentativi sono stati pubblicati in questi ultimi anni .

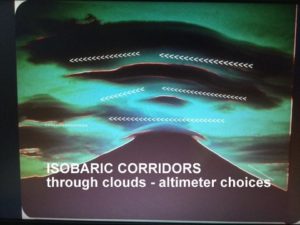

Se rilevante è l’elemento “ sbalzo della P.A. “ , altrettanto deve essere la verosimile condizione meteo-atmosferica che segue tale sbalzo e che sembra confermare per più ore/giorni la giustezza della decisione d’involo , dato che le condizioni di Alta Pressione – specie se realizzano un corridoio tra due aree di Bassa Pressione ( vedi schematizzazione di Alerstam ) – garantiscono condizioni di stabilità atmosferica in assenza di turbolenze , tutte condizioni che garantiscono risparmio di energie pur in lungo o lunghissimo volo “battente” migratorio .Se le condizioni di vasto corridoio di Alte Pressioni in mezzo ad aree cicloniche , si protraggono per molti giorni e su interi segmenti di Continente ( vedi figura …. ) , allora può anche verificarsi una massiccia e continuativa migrazione continentale come si è verificato nell’Ottobre 2017 .

Focalizzando l’analisi su “Picchi” migratori –quasi sempre molto localizzati per aree d’involo e transito – dobbiamo possibilmente indagare sia l’estensione di superficie dei corridoi aerei sia l’estensione altimetrica dei medesimi che di fatto costituiscono delle vie virtuali utili allo svolgimento aerodinamico del volo . Tali condizioni sulla nostra Penisola risentono fortemente dell’orografia in particolare trans-Appenninica .Bisogna inoltre ricordare che altri fattori abiotici incidono in qualche misura – oltre alla significatività di prevalenza statistica ( vedi P.A.) – nella fisiologia degli “echi sensoriali” : temperatura,umidità,soleggiamento,visibilità,venti,nuvolosità e precipitazioni , nonché durata della luce del giorno,fasi lunari ,disturbi da antropizzazione del territorio , variazioni dell’elettromagnetismo terrestre .

Molti di questi fattori sono stati considerati in dettaglio statistico crudo in precedente Lavoro “ Decision making of autumn migrations of Woodpigeons ( Columba palumbus) in Europe : analysis of the abiotic factors and “focus” on Atmospheric Pressure changes “ (CavinaE.,2014,on-line http://www.scienceheresy.com/ornithologyheresy/Cavina2015.pdf ).

L’argomento “ corridoi altimetrici” di percorrenza – dopo involi di massa – si presta a più dettagliata indagine ed analisi , coinvolgente la Meteorologia.

WORK in PROGRESS : suggestions welcome